- Can you tell us a little bit about your experience and background with education and teaching? How did you get involved with teaching?

Reading. Bronte begins Jane Eyre with this:

“There was no possibility of taking a walk that day. We had been wandering, indeed, in the leafless shrubbery an hour in the morning; but since dinner (Mrs. Reed, when there was not company, dined early) the cold winter wind had brought with it clouds so sombre, and a rain so penetrating, that further out-door exercise was now out of the question” (1, Brontë 1847).

I didn’t know that I couldn’t wander until I read and after reading, I couldn’t figure out how.

Later in the 19th Century, Emily Dickinson wrote:

I dwell in Possibility

A fairer House than Prose –

More numerous of Windows –

Superior – for Doors –

(466)

A teacher showed me the way towards dwelling in possibility and once I started my own journey, I wanted to be like them. Later I learned that poesy is truly a window, full of passage ways:

Poesy therefore is an art of imitation, for so Aristotle termeth it his word mimesis, that is to say, a representing, counterfeiting, or figuring forth – to speak metaphorically, a speaking picture; with this end, to teach and delight” (158, Sidney An Apology for Poetry 1595).

2. What do you love most about teaching? What do you believe is the most challenging aspect of teaching?

Possibility and Problems are always linked and don’t go away. Teachers are inventors. I learned from Henry Petrosky (who was head of Engineering at Duke at one time) the wonder of the inventors perspective. The great inventor Jacob Rabinow puts it this way: “Inventors are people who not only curse, but who also start to think of what can be done to eliminate the bother” (36). So Petroski asks what is going on inside these inventors, inside invention. He finds a network of attitudes, beliefs, and desires:

driven to make existing things better

uses mistakes as stepping stones

dissatisfied with what they see around them

avoids isolation: “the inventor who does not listen to others for stimulating ideas is usually a failure” (40).

Here is a lengthy quotation:

Regardless of their background and motivation, all inventors appear to share the quality of being driven by the real or perceived failure of existing things or processes to work as well as they might. Fault-finding with the made world around them and disappointment with the inefficiency with which things are done appear to be common traits among inventors and engineers generally. They revel in problems—those they themselves identify in the everyday things they use, or those they work on for corporations, clients, and friends. Inventors are not satisfied with things as they are; inventors are constantly dreaming of how things might be better.

This is not to say that inventors are pessimists. On the contrary, they are supreme optimists, for they pursue innovation with the belief that they can improve the world, or at least the things of the world. Inventors do not believe in leaving well enough alone, for well enough is not good enough for them. But, also being supreme pragmatists, they realize that they must recognize limits to improvement and the trade-offs that must accompany it. Credible inventors know the limitations of the world too, including its thermodynamic laws of conservation of energy and growth of entropy. They do not seek perpetual-motion machines or fountains of youth but, rather, strive to do the best with what they have and for the best they know they can have, and they always recognize that they can never have everything. (38, Petroski The Evolution of Useful Things, 1992).

Towards the end of the chapter, he suggests that inventors do two things: recognize problems (“Inventors are seldom at a loss for problems, and so they must choose which ones they will work on.” 37). and fashion solutions. They revel in the problems they can identify (a daughter of perfectionists). They dream for another way (a sister of cinema and poetry). They aren’t pessimistic. They believe that there are limits. They do not turn away from failure, change, longing. At the close of the chapter, Petroski suggests that inventors are overcome by a certain kind of love: the love of improvement, the love of alteration.

3. What do you wish more people understood about teaching/education?

“We do not see nature or intelligence or human motivation or ideology as “it” is but only as our languages are. And our languages are our media. Our media are our metaphors. Our metaphors create the content of our culture” (15, Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death,1985).

4. What can the new generation of educators learn from veteran teachers? What do you personally believe are some of the tried and true methods and considerations that will never go out of style?

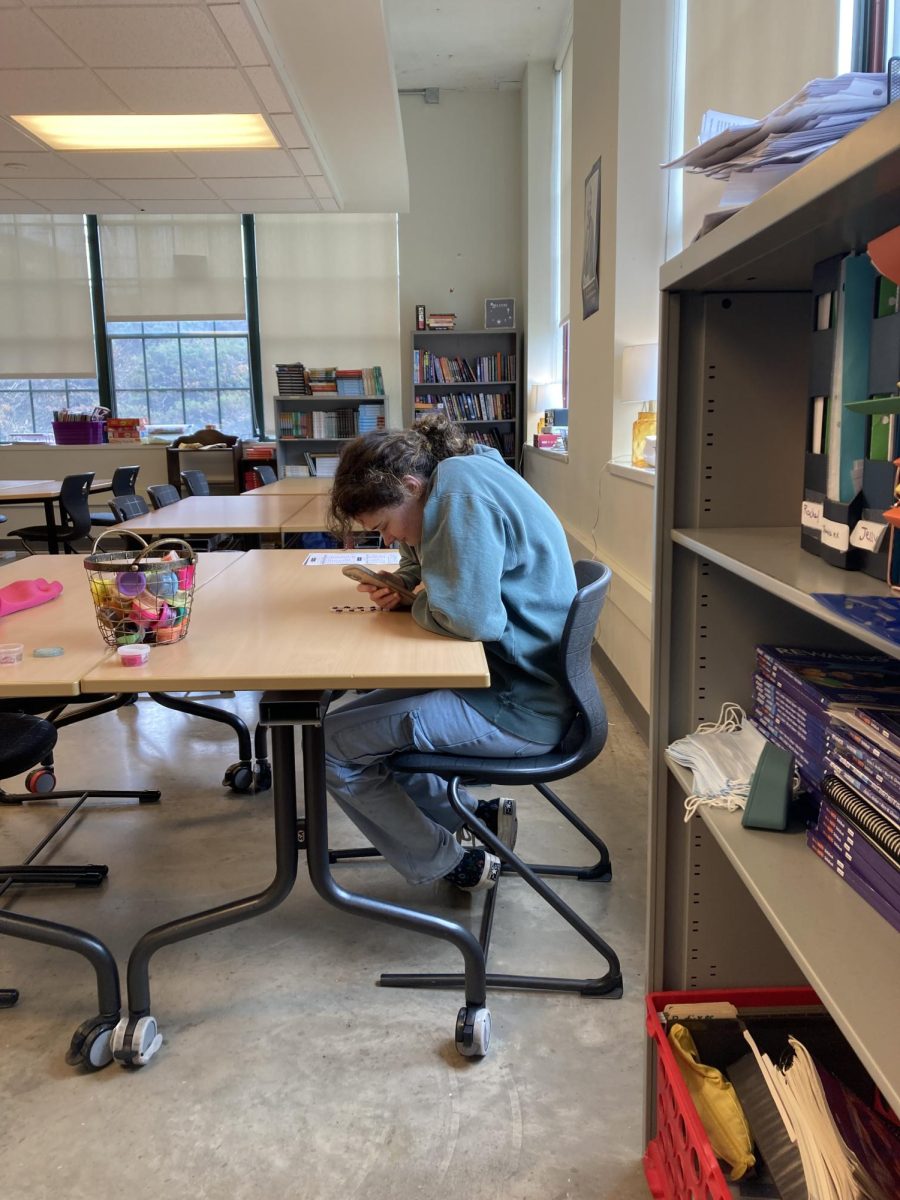

“I read a lot period” – Lauren Oalampina in Parable of the Sower (15, Octavia Butler, 2015).

5. What is the most important thing educators can do for their students?

Understand that possibility and problems are the source of learning. And choice. As Morpheus says to Neo: You take the blue pill… the story ends, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill…you stay in Wonderland and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes ” (Matrix, 1999).

Looks like Wachowskis are readers…

6.Wildcard: Tell us anything else you would like us to know.

“In our haste to teach a subject matter, we sometimes forget that we are teaching, first and foremost, a complex human being. We shouldn’t be concerned as much with the facts we want students to know as with those processes that help students learn whatever facts they need to know. By posing unfamiliar problems that require students to see, talk, think and write, we encourage them to modify the cognitive schemes that they have developed and to adopt progressively more complex ways of knowing (108, Lindenmann, A Rhetoric for Writing Teachers, 2001).

And finally, all the responses above come from my reading life. Nothing was googled, actual books were opened, underlined quotes cited, books taken from Ikea bookshelves, some found serendipitously, others were a gift, and yet others from materials I have used in classes or studies over the years.