We’ve never been great at understanding each other. Not one person out of all five in my family has exactly communicated their intent seamlessly to their loved others—it’s not like my younger childhood wasn’t rife with interpersonal conflict, defined by futile struggle to be understood and accepted. It wasn’t intentional on my parents’ part, nor on my siblings’, I still loved them, and I heard they still loved me plenty, but a household filled with undiagnosed autism and ADHD was bound to be a little clunky in trying to comprehend why each other would make the mistakes they made.

Me and my father particularly. My mother’s gotten much better at explaining and empathizing with the way I think (and knows me about as well as I know myself), and my siblings have gotten more forgiving. But he and I have had a growing rift the past couple months… the past couple years? I can’t tell. I haven’t been so nice about trying to see through his eyes, either, so I’m not here to say the results of miscommunication are all on him. It’s always seemed to me like no matter what nice moments we have together, he eventually always misinterprets my motives, takes me to be disrespectful when I’m just being frank, makes a joke I don’t see as “funny” …or misgenders me. Just because he messes up sometimes, doesn’t always get it right, I feel like he must not be able to understand me at all. Must not actually be trying, even if he claims it. It’s not that I hate him, and it’s not clear externally that there’s anything wrong. But he’s noticed, I’m sure—and in trying to put himself closer to me, caused more of the same misunderstandings that led me to put distance in the first place.

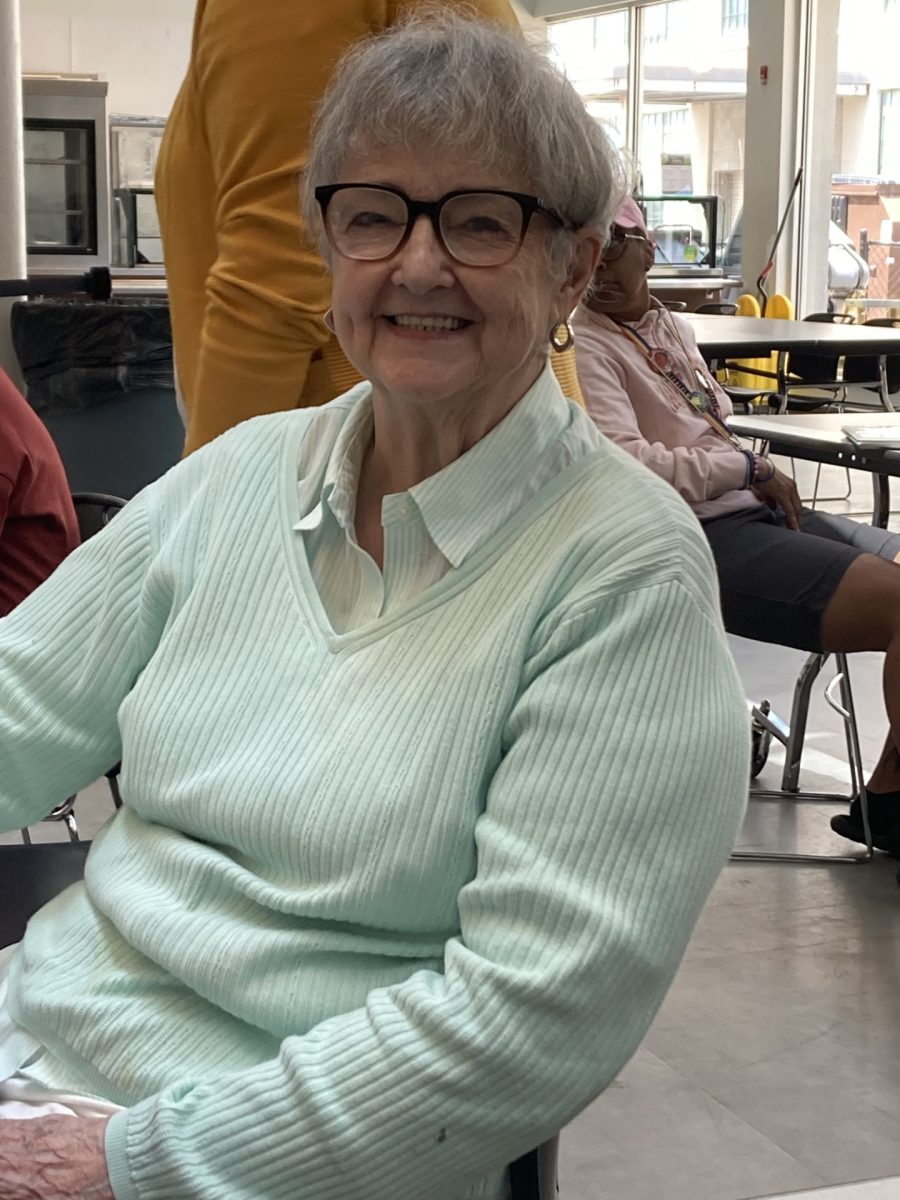

Five weeks ago, we flew impromptu to Arizona for a few days with my dying grandpa. I got to see that side of my family again—and connect with people I’m lucky to get chances to know again, living on the other side of the country. My dad had to see that side of his family again—and pick up after their messes again, even after moving away to the other side of the country.

It was not an easy time for anyone, but my grief was subdued and if it ever showed, I was sure it’d take some delay. I did actually have an excuse there, not knowing him well before his death. Not having much to cry about. I was not the man who had to handle his will, his life insurance, his plans after death, plane bills, and family drama on top of losing his father. He had a lot to take care of with my grandmother and his brother, intense people as they were loving. Might as well let him deal with one less miscommunication-prone, argumentative family member for the moment.

Discussions with my dad were unusually bereft of abrasion and of assuming the worst intentions during this time, especially after my grandpa finally passed. His innocuous jokes went without pushback, conversation stayed casual when it was the two of us, and even his tone seemed gentler. It was nicer, lighter if only for a time. My cousins and great-uncles had another hand holding theirs as it shook, another pair of arms around their back to lean into. It was easy, when you had the driest eyes in the room and still had love to give.

It was still a fight to keep myself from fighting him, but you really have to give some space in such a circumstance, no matter how much he dealt with grief as a comic and not a pauper. Logically, I knew how much it would help to give grace and allow forgiveness right at the moment, how much it was a good thing to foster even when everyone’s a little more emotionally stable. But I still kicked against “playing nice” like a colicky baby, still bided my time till I just had the chance to stop talking to him again.

Was a fight, until our final hours spent in Arizona—what better way to round off the trip than picture day at NAU?

Here’s a fun tradition my grandmother, an old medicine woman of the Kaqchikel, still holds onto: group pictures in our family always came with one “all the men”, and one “all the women”. In her eyes, I had made a dishonorable mistake: placing myself so gleefully among the men. And tradition is not something to be disregarded.

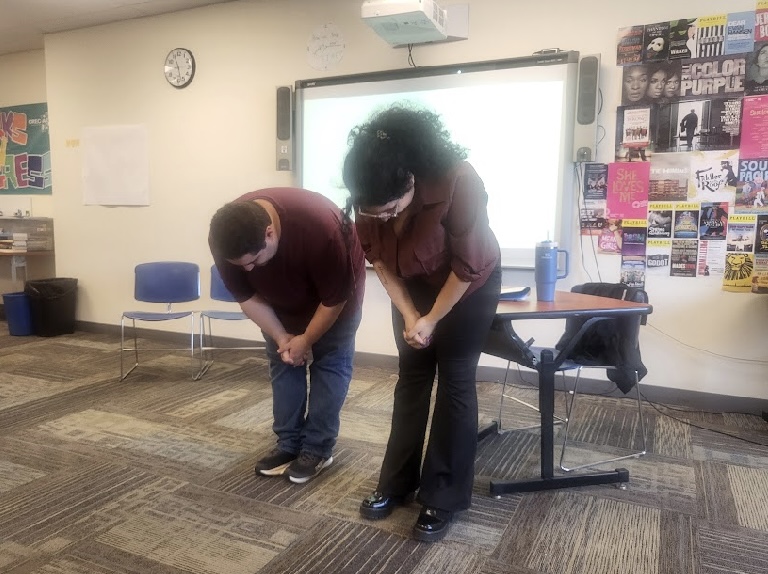

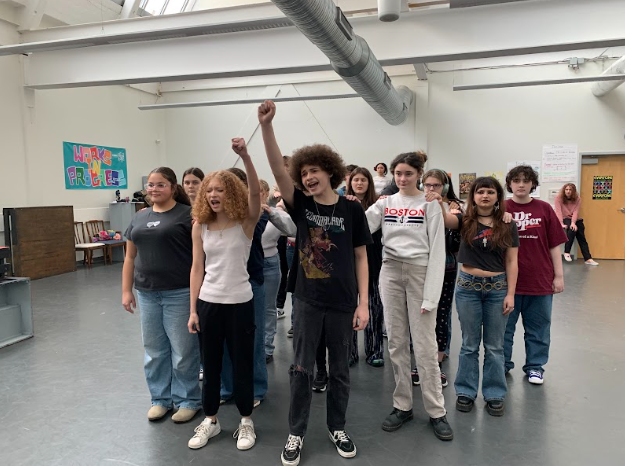

I sat still to be included with the women of the family, too, but I had made a decision that goes against everything they saw me as and I’m sure it looked like a frivolous joke to our matriarch. I’m 4’11 and thin, with long hair and a bright palette. It’s hard to see me as a man, if even “boyish” fit—I couldn’t explain to them how much more comfortable I felt in a picture with my great-uncles than my aunts, nor could I reason why. As much as I hold it against my father, I’ve never felt the confidence to establish myself. But we went about the rest of the pictures, and finally collected all of ourselves once again in the library to see Papa’s framed picture together, an award for the work he’s done and the lives he’s touched during his time as a professor. We listened to a former student of his who had only good things to say. We met another Vasquez, though of no relation to ourselves, who took our pictures and gave his condolences. Out of fifteen people, my grandma and I were the only two short enough to fit our heads under his frame. As we took our last family pictures with him I let it sit above me like some sort of peaceful halo.

That was around when I noticed my dad and uncles had all slipped out of my vision. Talking to the side, I wasn’t sure about what. I wasn’t bound to be paying much attention to my surroundings when that air of reverence still hung around me.

Again, I took my picture with the men (and with my cousin, who I wouldn’t call mature enough to be a “man” exactly) without conflict. Not before my father came up to me, a little teary.

I would hear them argue about it late into the evening, and hear him complain to my mother about how my grandma was being unreasonable in not budging on something, about how everyone deserved to do what was most comfortable…about how this wouldn’t be what my Papa wanted, not when we’re meant to be gathered to celebrate him and especially grave-rolling with the work he’s done and being the tolerant man that he was.

All in the moment, though, first he just hugged me. And then—for a man who still calls me she and her most of the time, who doesn’t understand why anyone would want to be a man—he told me that while my grandma would inevitably hang up a different set of pictures, I had the freedom to stay with whoever I wanted.

“I just asked her why my brother would get to have a picture with his son, when…” He was choking up a little here, and then he laughed. “…I’ve never said this before, but I wanted one with my son, too.”

…

We don’t fight so much anymore.

(And for the record, I almost cried, too.)