Parenting is one of the most powerful forces in a young adult’s life. Parents instill the values, customs, and beliefs that shape them as they grow into adulthood. However, what many parents don’t consider is the equally powerful force of advertising. Due to the constant exposure to countless carefully crafted advertisements, the influence of advertising can often outweigh that of parenting. This becomes clear when examining the effects of advertisements’ portrayal of gender roles. A girl could grow up being constantly told by her parents that women are equal to men, but if every time she opens a magazine, she rarely sees a woman doing the same actions as men or only ever sees a woman being used as an accessory, why would she believe them? And in the same vein, a boy could grow up being told by his parents to respect and not objectify women, but if every time he opens a magazine, women are being portrayed as supportive figures or sexual objects for men’s pleasure, why would he believe them? This isn’t just a hypothetical either; this happens all the time.

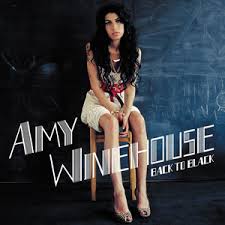

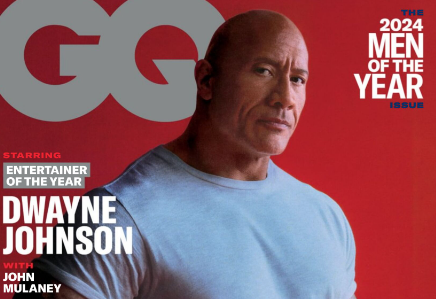

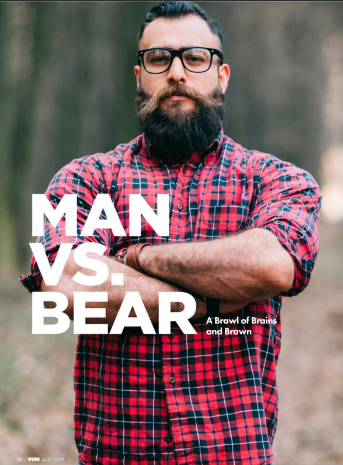

In the most recent issue of GQ, Men of the Year, the first time a woman appears in the magazine is for a Prada ad on pages 13-14. The ad is of two men and one woman smiling while sitting at a table.

This ad isn’t overtly sexual, but there is a clear power dynamic. The men are in the foreground while the woman is in the background. The men have open body language and are leaned back while the woman’s arms are crossed and she is leaned forward. The men aren’t looking at the woman, and their bodies aren’t facing her either, but she is looking at one of them, and her body is facing the other. The combination of these aspects subtly reinforces gender norms: the woman is submissive and positioned in support of the men, the men are dominant and barely acknowledge the woman. Given that GQ is a male-centered magazine made for men, the placement of any woman is going to immediately stick out. Since this is the first inclusion of a woman in the magazine, the contrast is even more striking and essentially sets the tone that in this magazine women will only be included if they are submissive and if a man needs implied support.

“The Ultimate GQ Holiday Wish List.” The next time a woman appears, on page 47, she is sitting on a man’s lap. She is wearing a low V-neck dress and heels; the man is wearing a suit. The ad, which is actually for the clothes they are wearing (see black box on left of ad), is overshadowed by a black bold caption that reads, “The Ultimate GQ Holiday Wish List.” The stark contrast of the words, the placement of the caption, the layout of the ad, and the body language of the man and woman make it seem as though the woman is a part of the “Ultimate GQ Holiday Wish List” or that the status the man has acquired through having a woman on his lap is a part of the “Ultimate GQ Holiday Wish List”. The way she is deliberately sitting on his lap, with his hand on her legs, makes her seem like an accessory and furthers the precedent set by the previous ad: women will only be included in the magazine if they are submissive, sexual, and supportive of a man.

This precedent isn’t exclusive to actual women either. Even women products are only included to imply submission or to support men or men’s products.

From pages 62-64, an array of Amaffi perfume is displayed. The first three are titled “Havana,” “Intrigant,” and “Hot heart” for men. Then, “Sultry Jungle” for women and “Tropical Rain” for men. Finally, “Chantage,” French for blackmail, and “Amor & Psychea,” French for love and psyche, for women. The names of the men’s fragrances convey strength and allure while the women’s fragrances suggest mystery, sensuality, and sexuality. Additionally, all of the men’s bottles are structured and go with the nature theme while the majority of the women’s bottles are curvy and “feminine,” one of them having legs and heels on them and one of them being a heart. This subtle reinforcement of gender roles furthers GQ’s message of women being secondary to their male counterparts, while also subtly introducing sexual undertones that associate women’s worth with their physical appearance and sexual appeal. Again, the mention of women is rare in this magazine. So, to only mention women when mentioning sex or sultriness or their relation to men shows that, once again, GQ clearly believes and wants their audience to believe that women will only be included when they are submissive, sexual, and in support of a man.

Now, you may be quick to think that this is all a coincidence, that GQ is unaware of the implication of their ads, or that they don’t intentionally target any specific group of people. But in reality, they know exactly who consumes these messages and exactly what impact they want these messages to have. To understand this, you must first know that advertisers like GQ extensively study consumer behavior to create targeted messages that are perfectly designed to influence and shape consumers decisions. The Persuaders, a Frontline documentary by Douglas Rushkoff, explains this process. In the documentary, Douglas reveals that advertisers use focus groups, research sessions where consumers give feedback on products; unconscious codes, subtle and often unnoticed cues designed to evoke emotion; and narrowcasting, a practice that targets audiences with personalized figures, messages, and ideas. GQ is no exception. They make deliberate choices to tailor to and influence their male target audience.

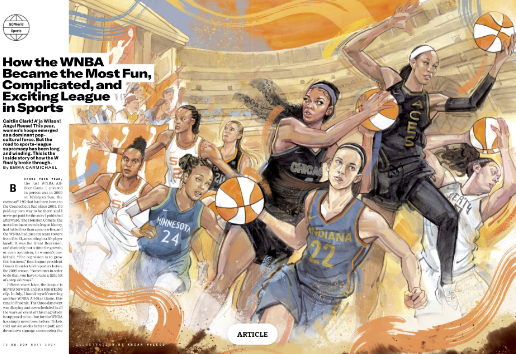

On pages 74-75, they include an excerpt about the WNBA, highlighting its success in 2024 and congratulating the WNBA players for this success. When I first went through the magazine, I was shocked to see this. Why would GQ, a male-centered magazine, talk about the WNBA instead of the NBA? Then I went to the next page.

Directly after, on page 77, GQ decided to include an ad for GQ Sports that features prominent NBA players Russel Westbrook and James Harden, not WNBA players. They also decided to put in bold white font that “The Real Action Is OFF The Court.” By doing this, GQ implies that the WNBA’s success and impact are insignificant in comparison to the success and impact of the NBA, even off the court. Here, they use the persuasive techniques outlined in The Persuaders. Just like narrowcasting, where advertisers use specific figures to target an audience, GQ uses the presence of the NBA stars to draw in their male audience, present their message, and influence them to believe, again, that women are only included to be submissive or to support a man.

Though these ads clearly reinforce harmful gender roles and misogynistic ideas, this still doesn’t explain why these messages are so powerful. How could an ad be powerful enough to outweigh the influence of people’s own parents?

The answer lies within the five key concepts of publicity and media. Concept 1: All media messages are constructed. Concept 2: Media constructs images using their own rules. Concept 3: People experience the same image differently. Concept 4: Media have embedded values and points of views. Concept 5: Media messages are organized to gain profit and/or power. Concepts 1 and 4 are what give magazines like GQ power. GQ chose and actively chooses to construct their magazine using specific imagery, wording, and placement. Nothing is unintentional. The Prada ad with the submissive woman wasn’t included because that’s the only shot they got, because companies spend hours doing photoshoots and editing. The WNBA and NBA contrasting pages were not placed there because they ran out of space; they choose how much space they use. The women’s perfume names were not mainly in French because they didn’t know how to translate; they chose to keep the names mysterious. Through this construction, they embed values like women being submissive, men being dominant, and women being seen as sexual accessories constantly. This embedding is so constant that if a young adult picked up a GQ magazine 10 years ago, they would see the same imagery, wording, and placement. As people, if we are told and shown something constantly, we are bound to begin believing it and might even try replicating it. Also, when we see the people who are deemed successful embodying these embedded values, we might try replicating it. Either way, we would be influenced. Now, imagine if your young adult son or daughter is constantly surrounded by this environment. As feminist scholar Jean Kilbourne explained in Two Ways a Woman Can Get Hurt, “advertising often encourages women to be attracted to hostile and indifferent men while encouraging boys to become these men.” (Kilbourne 424). I’m not saying all of this to be bleak or discouraging. Instead, I hope this serves as a reminder to parents of the powerful, pervasive force of advertisement you’re essentially competing against when raising your child. By recognizing these influences and messages through open conversations and guidance, you can help your kid critically analyze what they see and, as a result, be less influenced by it. In the end, your child will thrive.