As a teenage girl, looking to the future is scary. Beyond college, moving out, and becoming an adult, we have to find our place in the world. 18-year-olds who sell themselves the second the clock strikes midnight tell us womanhood is sex and only sex. Parents tell us, “It doesn’t have to be like that,” before we know what that means. Media gives a delicate in-between. Their mission? To tell you your role in society without you realizing it.

In America, sex is stigmatized until someone can profit from it. Female fulfillment, even more so. We’re so stuck in our own biases that this seems normal. Looking beyond the US, other countries have very different views. We look at those with conservative views and shudder, then settle back into our own. How do more progressive countries view us?

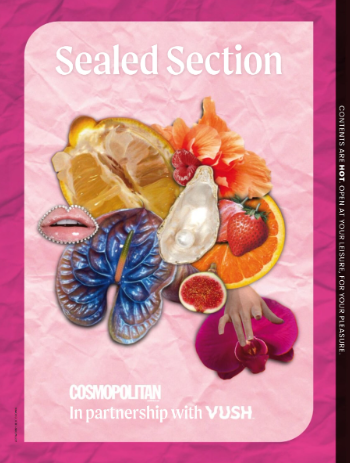

Cosmopolitan magazine is very popular in the US. Designed for women ages 18-35, it offers teen girls a glimpse of what’s next. However, the media sends us messages constantly, so simply rifling through a magazine can cause irreparable damage to one’s psyche. While American issues of Cosmo feature countless men as if that’s all we care about and show half-naked women next to advertisements for household items, Cosmopolitan Australia has a much more neutral approach. With one single man in the entire issue and limited contorted poses, it appeals to normal women much more than the highly fetishized American line. Cosmo Australia seems to understand our third key media concept, audience, much better than Cosmo America; with its realistic lens, it matches the audience’s sexual experiences. Cosmopolitan magazine is inherently sexual, no matter its country of origin. I feel that the incorporation of day-to-day life into the American version sends the message that porn-like sex is regular, while the Australian version shows sexual experimentation as cheeky and fun, but not required. Beginning with the section cover to their more explicit content, they acknowledge that not everyone wants to read this part of their magazine. The Australian Cosmo says that sex is for you, not for the world.

The realistic view of sex in Cosmopolitan Australia is refreshing. The magazine is a safe space for women. In the advertisements as well as the photos of women in the articles, they’re all confident and happy. The majority of them demand your attention with direct eye contact. It’s so typical to see models in over-sexualized poses that the smiles in this issue seem somewhat unusual.

These women are happy. When was the last time you saw a model smile? When you ask teen girls who are scared of the future how they want to see themselves in five years, tell me they don’t say happy. Cosmo Australia gets down to the essentials. The basis of life is the pursuit of happiness, is it not? John Berger writes, “The state of being envied is what constitutes glamour” (131). It’s not their beauty you’re meant to envy, it’s their joy. Not to be corny, but their smiles make them glamorous. Subconsciously, we want what they have, because happiness for women is so out-of-the-ordinary in advertisements. What makes them so special? Whatever the product is, we want it.

The celebrities and popular media featured in this magazine are ultra-curated to Cosmo’s audience. Young women are moths to the flames of Millie Bobby Brown, Hunter Schafer, and Sex and the City. Flip open to practically any page of this magazine and see something or someone you know; the products being sold are also specially chosen for this audience. Every single page is made just for you; how could you resist? Narrowcasting is invasive to some, but no one can deny that its return is something you want. This magazine accepts you for who you are. It encourages your interests without judgment, creating a haven for women within Cosmopolitan.

However, there is no perfect world. There is no perfect magazine, in which women aren’t the products being sold. Even when we travel the world and find a place that’s better, there’s always a give and take. To be open about female desire, we inadvertently add to the patriarchal mindset that all women want is sex (Kilbourne 435).

This is an ad for sneakers. She’s wearing bikini bottoms, legs spread, mouth open. She’s out for a run, in bikini bottoms. At least she has that hoodie to tie around her waist! There is no logical reason for her to be wearing that, only to make her sexier to the viewer. These sneakers will make you sexier, the company is saying. Our eyes are not drawn to the sneakers; in fact, they’re the last thing you see.

At first glance, this may seem like a natural pose. Take another look: she’s making herself smaller. She is simultaneously shy and confident, innocent and wanting sex. For Cosmo Australia to portray women as human, the multitudes we contain will always center around sex. So, do they actually show women as human, or still sex objects? It could be argued that we’ve looped back around into the extremely outdated belief “…that all women, regardless of age, are really temptresses in disguise, nymphets, sexually insatiable and seductive” (Kilbourne 435).

Upon further inspection of this issue, not all the advertisements are as empowering as Cosmo would like us to believe.

In this Sally Hansen ad, the word “fling” in the bold print, “Have a Summer Fling with Colour,” reminds us of sex. It’s fun and carefree sex, yes, but an intrusive reminder of what society thinks of women. They can’t even disguise it as her choice anymore: her face isn’t included, just her body (in another string bikini, mind you). And while an Australian summer does come with extreme heat, the snow cone she’s holding isn’t to cool her down, but to make her even hotter to us. A seemingly innocent ad for colorful nail polish becomes exploitative upon a closer look.

The phallic image paired with the word “fling” and her exposed hip forces us to think about her sexually. If we could see her face, it would be clearer if this was intended to be so suggestive, but we can’t, so it’s up to us. And when it’s put up to interpretation, bias – bias learned from ads just like this one – tells us it’s not, and everything is okay. We don’t see it as sexual because the company wants us to, but because it’s there.

The careful curation of ads, as well as other media, sends us the message that women are sexual objects. However, because of this care they take, and because of how casually these ads are often taken, we don’t usually realize. It’s somewhat of a subliminal message, and simply taking more than 15 seconds to look at an ad is the equivalent of playing the record backward. It’s not our fault that we’re drawn to sexualized content, because companies have trained it into us. When we realize odd things in these ads, we tend to think it’s unintentional, or that we just have dirty minds. Because they’ve trained it into us. As long as we think the companies aren’t to blame, as long as we don’t see how they perpetuate the horrid societal views of women, they own us. We click the links and buy the sponsored products and earn them their commission, and they get what they want. Our money, yes, but more importantly, our complicity in allowing them to control our lives.

Magazines used

Australian issue https://libbyapp.com/search/libraryconnection/issues-11166325/page-1/11214629

American issue https://libbyapp.com/search/libraryconnection/search/query-Cosmopolitan/page-1/11326000