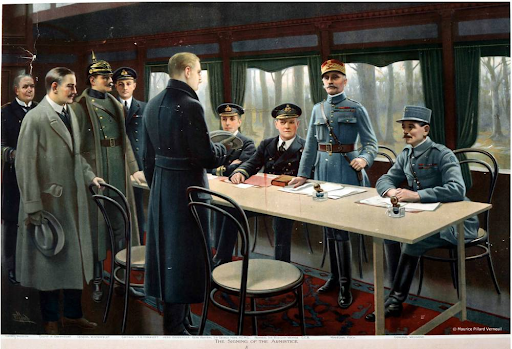

A rendition of the Armistice’s signing is shown above.

105 years ago, the world’s largest and most fatal conflict yet ended with a ceasefire between the Third French Republic and the German Empire.

20 million deaths, more than twice that wounded.

The fall of four empires.

A reformed status quo – a democratic Europe, with almost no absolute monarchies in sight.

The rise of two of the most powerful nations, ever.

The direct cause of the most well-known and destructive war in history.

All of this from a single war:

The Great War.

The Armistice of Compiégne was signed five hours and fifteen minutes before it went into effect – on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. 2,738 troops died needless deaths in those five hours and fifteen minutes, the last an American who died just a minute before the eleventh hour. 2,738 of 20 million deaths in just over five hours. Nothing anyone had seen before in five millennia of human history. And yet, the only reason most people know that there was a world war before the Second World War was, well, the second world war. There had to be a first, but nobody knows what exactly went on.

So let me set a stage:

The world was shaken to the ground after the Napoleonic Wars, and Europe barely managed to create a delicate and masterful peace between the Great Powers of Europe. However, multiple issues rose during the century between the last Napoleonic War and the First World War: Prussian militarism and goals to unify Germany, pan-European revolutions aiming to create democratic states that represented peoples from Hungarians and Germans to Poles and Slovaks, and the Great Powers falling into two major factions.

A map of post-Napoleonic Europe is shown above.

So, the stage for war was set – and the first shot that would kill millions was fired on June 28, 1914.

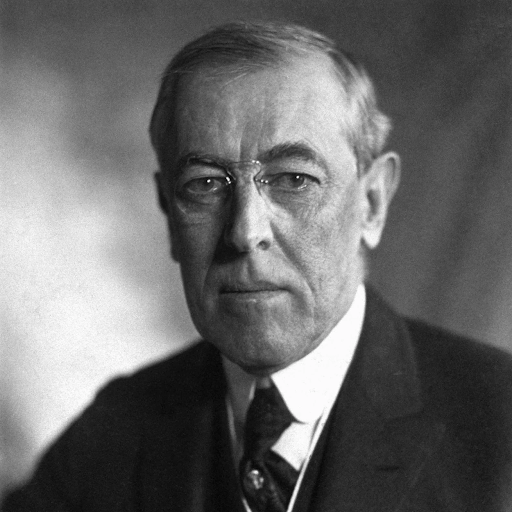

Skipping past four years of constant, brutal, terrifying warfare, the German Empire was felled by a revolution that finally installed a democratic government, based in the city of Weimar. The United States had finally joined the war in 1917, and Woodrow Wilson, the American president, had brought his ideals into the Paris Peace Conferences. He was fierce, and did his best to, over anything else, give the people of nations their own countries – under democracy.

US President Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921)

These two points, while admittedly not without their merits, were poisoned by the way Wilson – and eventually his successors – ran with them. His justifications for joining the war were not just due to the sinking of American ships by the Germans or the promise of US states to Mexico by Germany, but rather his Fourteen Points (National WWI Museum and Memorial), including the idea of spreading democracy and self-determination – by force. Do you see any similarities to today? American power has been shown around the world, with the advent of useless wars attempting to place democratic governments in power, and other governments they don’t agree with (even fully democratic ones) being destroyed in favor of ones that may prefer the USA. A legacy of US imperialism all starting with one man.

Hundreds have died from unexploded weapons in Laos since the Vietnam War, since Laos was having a communist uprising – how undemocratic – and they were allied with Vietnam. Laos is now the world’s most shelled country, with over 270 million munitions being fired at the country, and up to 80 million of them have never exploded, according to Legacies of War. Cambodia similarly suffered due to American bombing during the same war, with the bombing campaigns being one of the major reasons for the rise of the heavily oppressive Khmer Rouge, who killed from 1.5 to 3 million people, according to the University of Minnesota’s Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

Looking towards Europe, it’s impossible to ignore Hungary. It’s a nation that has existed since 1000, to varying degrees of independence and governments. What didn’t vary until the Great War – technically excepting for a century-and-a-half-long period where a Muslim empire completely controlled Hungary – was Hungary’s territorial boundaries. However, according to the BBC, after Wilson’s idealism caused the releasing of ethnic minorities from Hungary – Romanians, Croats, Serbs, Slovenes, Slovaks and even Austrians, who lost the war too – Hungarians felt that they were the only exception to the idea of self-determination. Several regions lost in the Treaty of Trianon had Hungarian-majority areas, ones that even had massive cultural impacts. These lands were taken by the victors of the war, some of whom used Wilson’s major oversight in his idea of self-determination: he didn’t even know which areas actually had ethnic majorities.

A map of ethnic majorities in Hungary, 1910 (Both the Kingdoms of Hungary and Croatia-Slavonia)

The impact is seen today, as Viktor Orbán, the accused dictator of Hungary, has an aggressive, nationalist foreign policy dating back to the end of Hungarian communism in 1989. He’s placed himself in a neutral position to the Ukraine War, blocking EU humanitarian aid to Ukraine, according to GIS Reports Online. He even wore a scarf which featured an image of “Greater Hungary,” the term that refers to the historical territory of Hungary in 2022, sparking a controversy in which Romania, which held a large amount of the land that Hungary lost after WWI, and Ukraine, which holds a region in the Carpathians that was given to Slovakia after the Great War, eventually ending up in Ukrainian hands.

These topics cause massive issues and deaths to the modern day, and have been so since the war’s end more than a century ago. And, even though the war happened a century ago, we still feel the impacts, from the lives of billions to the tracks nations were set on by the war, and of course, the irredentism of many nations.